Veterinary Medical Report from the Field – Investigating Human-Animal-Interfaces at a Nigerian Abattoir

It’s 7am, somewhere in the outskirts of Abuja, capital of Nigeria. The sun just rose an hour ago, but already now we can feel that it is going to be a hot day, up to 40°C. It is the end of dry season, and every living being, human, animal and plant alike, is craving for the first rain to fall.

We arrive at our field site: the compound of one of the biggest abattoirs in the country, including a live animal market and a meat and grocery market. The air is thick with dust, and the whole place is busy and vibrant already. Most people are awake since 5am, time of the morning prayer, with which the daily work commences at the abattoir.

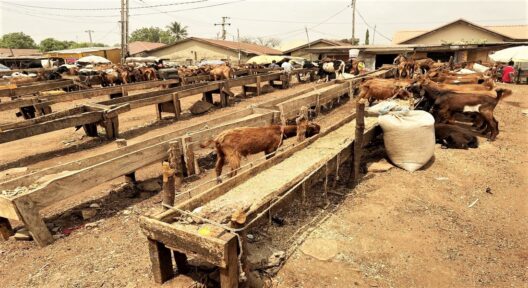

We are entering the compound to walk to our meeting spot next to the slaughter house through the live animal section. At the entrance, a truck is parked next to a loading ramp built from earth, and we find ourselves in the middle of the process of unloading of cattle. While some are already unloaded, gazing with exhaustion and confused at the new scenery they landed in, others are still lying on the truck, with legs tied to withhold them from moving during the long journey. We learn that they were bought on a market in a federal state in the North, where the prolonged dry seasons combined with the fuel scarcity and increasing inflation is forcing the farmers to sell even their last female cows. From the signalment of the animals, we get an idea of the difficulties farmers have to deal with in the North. They are close to emaciation, and many of them first need to drink a bucket of water until they find the strength to stand up again. Carefully watching our steps, we continue our path through the lairage. Here, cattle of different breeds and sizes are tied to flocks, belonging to different dealers who stay in huts scattered at the border of the compound. Two men are leading a somehow recalcitrant bull towards the exit at the other end, behind which the slaughter house is located. We follow them in a respectful distance.

We, that are Hellena Debelts, an anthropologist from the Robert Koch-Institute, and Valerie Allendorf, a veterinarian from the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, meeting with our colleagues from the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and from the National Veterinary Research Institute (NVRI). Our multinational team works together in a joint field mission to collect data about interfaces between humans, animals and the environment. These data are supposed to shed more light on the potential transmission pathways of zoonotic pathogens, being part of people’s everyday life. Using SARS-CoV 2 as an example, we aim to show where potential transmission risks can be found by linking anthropological data with test results from human and animal samples, and to identify approaches to mitigate these risks.

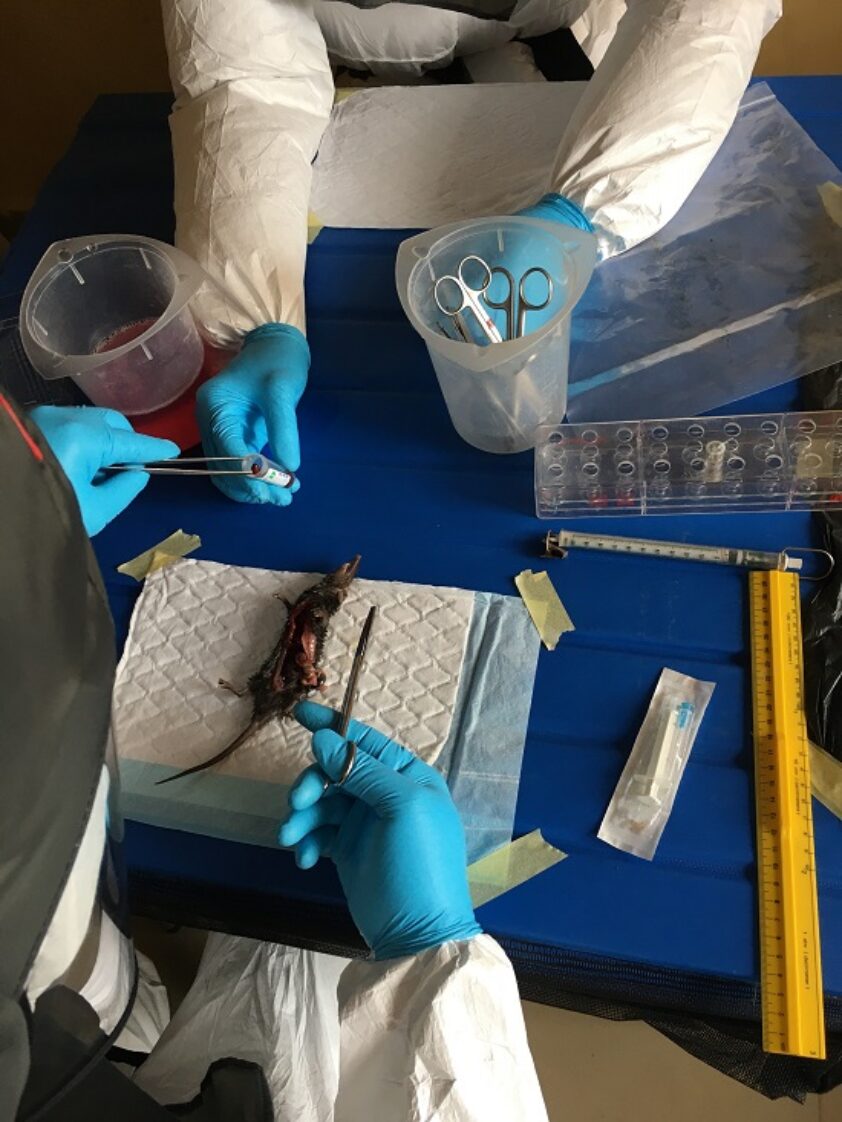

Our colleagues are already waiting in front of the office of the veterinarians deployed by the government to ensure veterinary public health at the abattoir. As we approach them, we see that they already started to recollect the small mammal traps that we set up the evening before. “Nice catch”, Jerry Ijomanta, one of the NVRI veterinarians, is greeting us smiling. “We caught four in and behind the slaughterhouse! The others are picking up the traps from the lairage. There they come!” Turning around, we see the two junior scientists Oluyemi Ogunmolawa and Joshua Seyi Oyetunde walking towards us, each transporting a bag with the retracted traps. On the lairage, the trapping session was not that successful, but there are more sessions to follow. We leave our catch for now, to come back to the dissection and sampling of the animals later this morning. While Hellena and Adeoye Adeponle, the anthropologist from NCDC, are leaving to conduct an interview with one of their key interlocutors, Olayinka Asala, Chief Veterinary Research Officer at the NVRI, is stepping out of the veterinarians’ office together with two veterinarians of the abattoir. “Let’s get going, guys.” We put on our protective gear and split groups: one half enters the slaughter house to sample cattle, while the other half proceeds to the goat slaughtering section located behind the slaughter house, next to small chimneys from which black smoke is ascending into the clear blue sky. The Malam, a specifically religiously trained man who is in charge of the halal slaughtering, greets us with a smile; he was already expecting us. Since the start of his working shift two hours ago, he already cut the throats of some hundreds of goats. Now, the frequency of slaughtering is slowly decreasing, we have avoided the hectic in the early morning hours on purpose. While exchanging some friendly words, a man approaches, followed by six nervously looking goats – the sign for the Malam to continue his work. While the goats’ legs are tied together and put on the floor one after another, we arrange our sampling material and get ready ourselves. The Malam picks up his long slim knife, and then steps towards the goats. Silently, he walks down the line of protesting animals, bending down six times to cut deeply into the throats. Bright red blood is splashing. Quickly, two of us are heading towards the dying animals, to collect samples of blood, nose swabs, and mandibular lymph nodes, while the third stays behind to manage and label the tubes. After what seems to be seconds, the now dead bodies are moved to the next step of the processing chain, the chimneys, where their fur is burnt off. The black smoke thickens, while the next small group of goats approaches and we prepare for the next round of sampling.

After two hours, the tide of incoming animals recedes. We close our sampling session for the day. There are more to follow. We meet up with the other half of the group, and after cleaning our equipment and ourselves, we leave the abattoir to proceed with the dissection and sampling of the night’s catch, and to store all precious samples in liquid nitrogen. One week later, they will be taken to the NVRI laboratory in Plateau State, where the lab analysis will be conducted to find out more about the network of beings and their pathogens within this very special but somehow common small ecosystem of the abattoir and beyond.

The complementary report examining human-animal-environment-interfaces from an anthropological perspective can be found here.

Date: July 2022